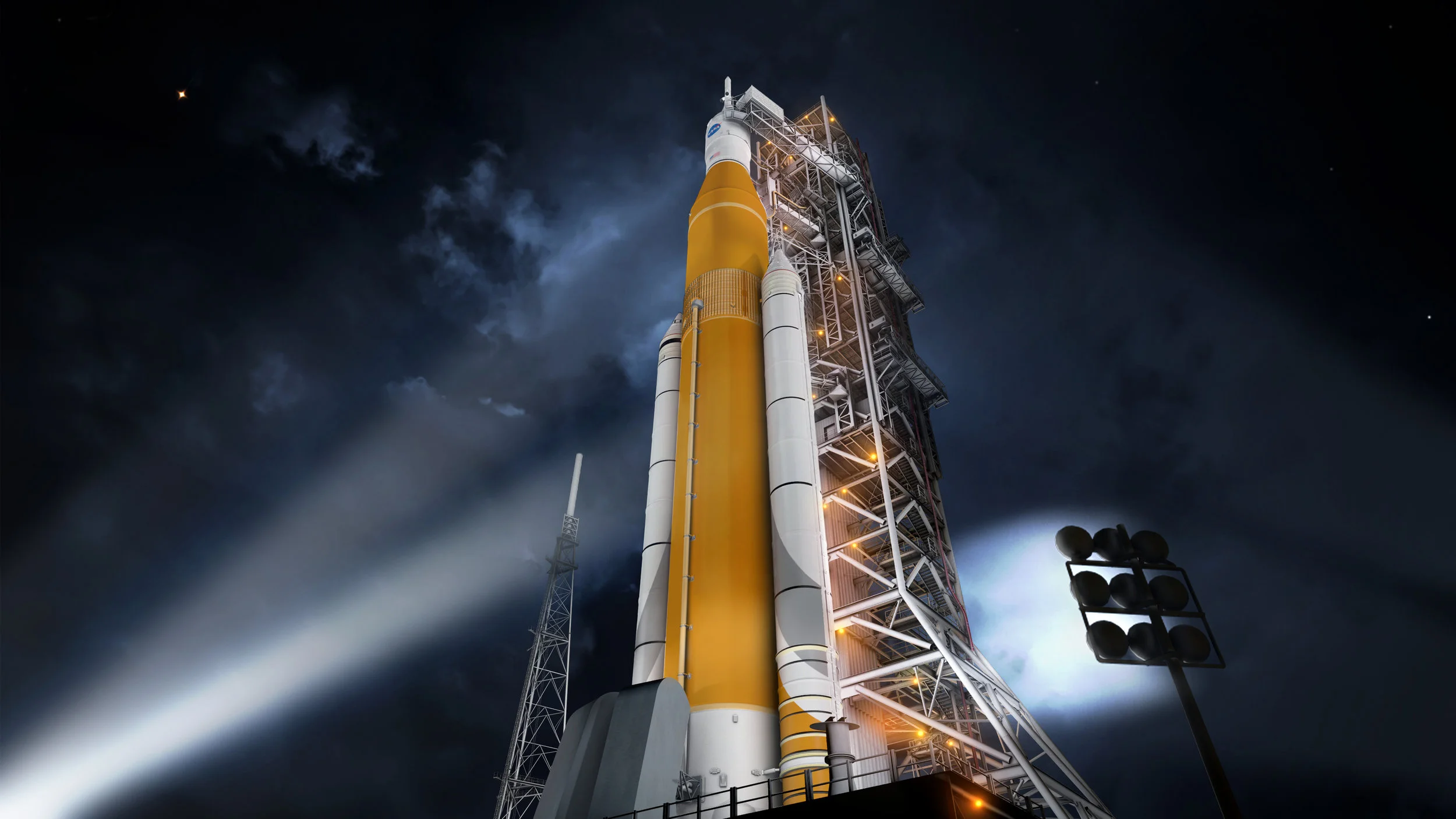

Facing further delays in the development of the Space Launch System (SLS) super-heavy lift rocket, NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine told members of the Senate Commerce Committee last week that the agency is considering launching its new Orion spacecraft aboard a commercial vehicle.

Responding to questions from Sen. Roger Wicker (R), Bridenstine admitted, “SLS is struggling to meet its schedule.” Wicker, along with other members of the committee, has a vested interest in SLS’s success. NASA’s Stennis Space Center, located in Wicker’s home state of Mississippi, is one of a handful of facilities across the country where components of the new launch vehicle are being built and tested.

March 13 Commerce Committee hearing - The New Space Race: Ensuring U.S. Global Leadership on the Final Frontier

Full video

This isn’t the project’s first delay. SLS has faced setbacks due to budgetary cuts, production delays, and a myriad of other factors. The SLS program began in 2010, birthed out of designs from the Ares V rocket and NASA’s Constellation program, which ran from 2005 to 2010. The rocket’s maiden flight was originally scheduled for 2017, launching Exploration Mission-1 (EM-1), which would send the space agency’s newest human-rated Orion spacecraft on a three-week trip around the moon and back. Delays in the rocket’s development had pushed EM-1 to June 2020, but now it seems that date will slip even further.

EM-1, while uncrewed, is NASA’s true first step into sustained human exploration of deep space, and SLS is the only rocket capable of fulfilling the needs of the space agency’s future missions. Ensuring the mission’s targeted 2020 launch date hits the mark, Bridenstine revealed NASA is considering “all options” to keep EM-1 on track. This includes launching Orion and the capsule’s European Service Module (ESM) atop commercially contracted vehicles.

“I want to be really clear. I think we, as an agency, need to stick to our commitments… If we tell you and others that we’re going to launch in June of 2020 around the moon, which is what EM-1 is, I think we should launch around the moon June of 2020, and I think it can be done. We need to consider, as an agency, all options to accomplish that objective.”

The most recent setbacks come following the Trump Administration’s FY2020 budget proposal for NASA, which calls for a 17 percent cut in SLS funding and a 9 percent cut to Orion. The briefing also defers work on the larger SLS Block 1B. Featuring a more powerful upper stage, the Block 1B is the only rocket NASA has in development capable of lifting the modules for its planned Lunar Gateway station. The proposed FY2020 budget instead focuses on the expedited production of SLS for upcoming launches, though it seems the new rocket will still miss EM-1’s June 2020 target.

Artistic rendering of NASA's Lunar Gateway Station concept. Image credit: NASA

Bridenstine’s statement that the agency is considering other launch vehicles for EM-1 came as a surprise to the commercial space industry. NASA has contracted SpaceX and United Launch Alliance (ULA) to design and launch human-rated spacecraft to ferry astronauts to the International Space Station (ISS), and Orion’s initial Exploration Flight Test-1 (EFT-1) launched aboard a ULA Delta IV Heavy rocket. Outside of those contracts, there was no indication NASA had planned to utilize any commercial launch partners with Orion for their deep space program until now.

EFT-1 launched Orion into a high Earth orbit to test the capsule’s heat-shield and other systems during reentry on Dec. 5, 2014. EM-1’s primary components, Orion and the European Service Module, are built to sustain human voyages to the moon and Mars. Launching the pair on a commercial rocket for EM-1 would still allow NASA to test the spacecraft’s systems, but not without some difficulty. There are some major hurdles to overcome if NASA wants to stay on schedule.

Bridenstine refrained from naming any specific launch contenders being considered to step in for SLS, but said the mission would have to be modified to use two rockets. While ULA’s heavy variant of its Delta IV was powerful enough to launch Orion for EFT-1, it lacks the fuel to get Orion to lunar orbit. Accordingly, Orion and the ESM would have to be launched as a pair, and a second heavy-lift rocket would need to launch a fueled upper-stage to dock with Orion and propel the spacecraft to the moon.

“We do not have right now an ability to dock the Orion crew capsule with anything in orbit…Between now and June of 2020, we would have to make that a reality,” Bridenstine said. That means developing the hardware and the software to dock the two stages together in orbit.”

For some context in time, the International Docking Adapters (IDAs) NASA contracted Boeing to construct for the space station took months to build, not to mention the time it took to design them. SpaceX and Boeing utilize these ports’ new International Docking System Standard to dock their Crew Dragon and CST-100 Starliner spacecrafts to the ISS, respectively. Sourced with parts from companies across 25 different states, the IDA has a diameter a little over 1.5 meters, and is just wide enough for astronauts to transfer out of their spacecraft and enter the space station.

International Docking Adapter, prior to launch (above), location on the International Space Station (bottom left), and docked with Crew Dragon during DM-1 (bottom right). Images courtesy of NASA.

Orion and the European Service Module are much wider (about 5 meters), and will likely need a completely new type of docking mechanism. The difficulties of creating a new docking system aside, these changes will also undoubtedly lead to alterations of the ESM, which is currently undergoing tests by Lockheed Martin at the Kennedy Space Center, in Florida. As a result, it seems inevitable that the service module will require some degree of further testing to certify whatever alterations the change in mission finally dictates.

June 2020 is fifteen months away. This is an aggressive timeline.

Even procuring a launch vehicle typically requires up to two years lead time. Though, reassigning a vehicle currently undergoing preparations for an upcoming launch isn’t outside the realm of possibility, and has certainly been done in the past to meet mission parameters. Given ULA’s long history with NASA, as well as their involvement with EFT-1, it’s safe to say the launch provider is a potential candidate. ULA was eager to throw their hat in the ring. Ars Technica Senior Space Editor Eric Berger tweeted a statement from ULA following last week’s hearing.

Another possible option is SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy. The private space company’s new heavy-lift rocket, with a nearly 70 ton payload capacity to Low Earth Orbit, could also lift the required components for EM-1. SpaceX currently lists five upcoming Falcon Heavy launches on the company’s website, and is expected to fulfill two of those contracts this year - the first as early as April 7.

NASA’s EM-1 Orion spacecraft under construction at the Neil Armstrong Operations & Checkout Building, 2016. Photo credit: Josh Dinner

Should the EM-1 schedule meet all of NASA’s expectations, the agency hopes to launch Exploration Mission-2 in June of 2022. If that turns out to be the first launch of SLS with Orion, it is unclear whether NASA would consider making it a crewed mission. NASA, which has not put astronauts aboard any vehicle’s maiden flight since the first space shuttle, briefly considered assigning a crew to EM-1, but ultimately abandoned the plan.

Now, more than a decade into NASA’s evolving plans to send humanity back into deep space and beyond the moon, the agency’s administrator wants to turn the tide. Bridenstine made it clear during last week’s hearing, “NASA has a history of not meeting launch dates. I’m trying to change that.” A decision on NASA’s use of commercial launch vehicles for EM-1 will come “in the next couple weeks,” Bridenstine said. “Every moment counts.”